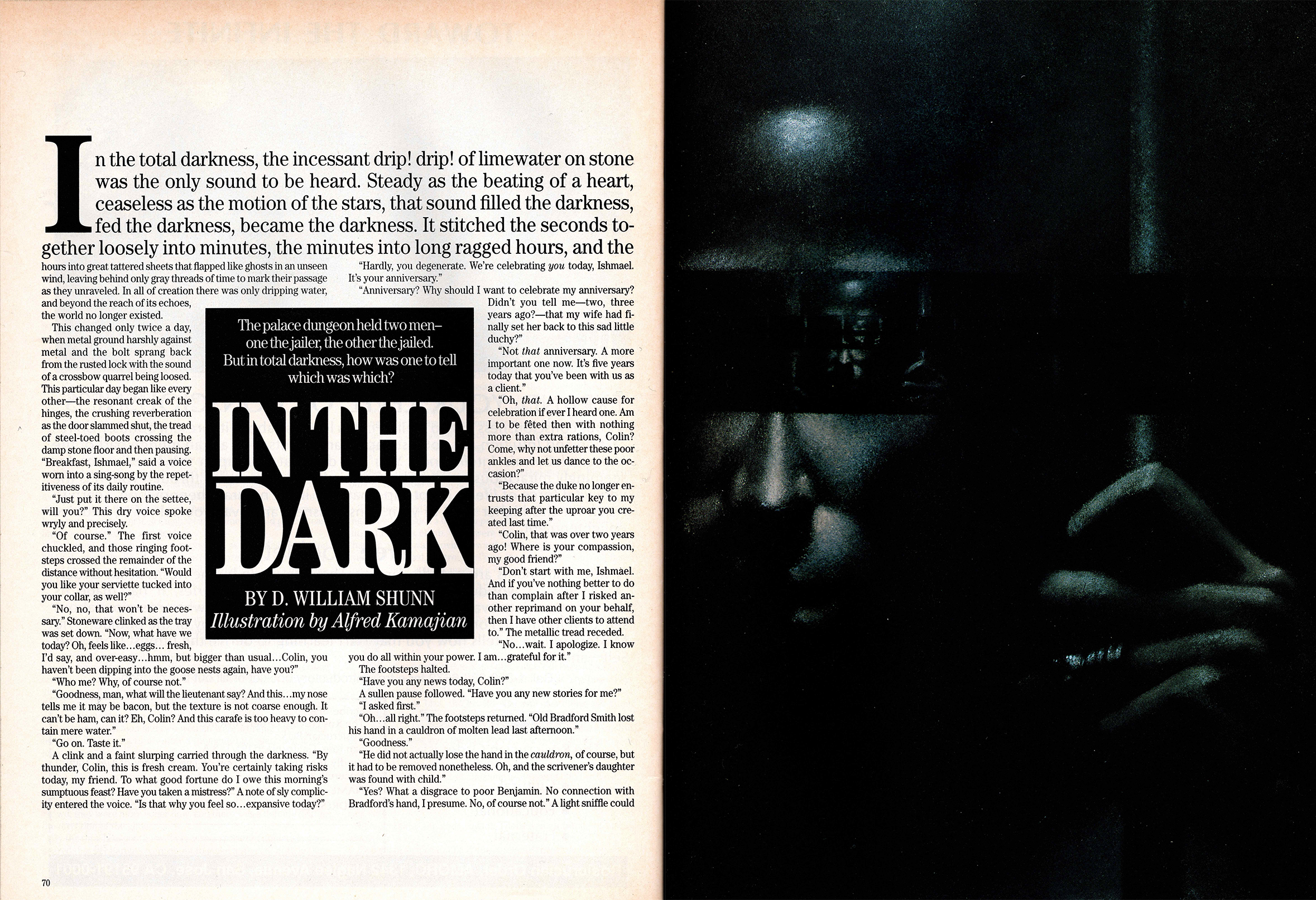

Colin and Ishmael in the Dark

A prisoner and his jailer play a game of cat-and-mouse in total darkness—but which is the hunter and which the hunted? Fiction for Halloween.

This short story began as an exercise in a college writing class at the University of Utah in late 1988. The instructor asked us to write a short scene set in a darkened room entirely in dialog. I wrote a couple of pages—much more than the exercise called for—of two characters talking in a dungeon. I liked what I had done, though I couldn’t think where to go with it next.

A year or two later, I was going through my class notes and found the scene. As I read through it, I could suddenly see how to move things forward. Over the next few days I raced through the subterranean confrontation between Colin and Ishmael, polished up what I had, and started sending it out to the major genre magazines.

No one bit until I tried Scott Edelman at a glossy new magazine called Science Fiction Age. In those early years of Age, Scott would buy exactly one fantasy story for every issue, and mine was apparently the right fit for the hole in issue six. I was delighted that “Colin and Ishmael in the Dark” had found a home, though I thought my original title was more evocative than the truncated version it ran under in print. Appearing in the September 1993 issue, the story was just my second professional fiction publication.

I’m grateful to Scott for buying this (and more stories too), and I’m glad we’re still friends today.

In the total darkness, the incessant drip! drip! of limewater on stone was the only sound to be heard. Steady as the beating of a heart, ceaseless as the motion of the stars, that sound filled the darkness, fed the darkness, became the darkness. It stitched the seconds together loosely into minutes, the minutes into long ragged hours, and the hours into great tattered sheets that flapped like ghosts in an unseen wind, leaving behind only gray threads of time to mark their passage as they unraveled. In all of creation there was only dripping water, and beyond the reach of its echoes the world no longer existed.

This changed only twice a day, when metal ground harshly against metal and the bolt sprang back from the rusted lock with the sound of a crossbow quarrel being loosed. This particular day began like every other—the resonant creak of the hinges, the crushing reverberation as the door slammed shut, the tread of steel-toed boots crossing the damp stone floor and then pausing. “Breakfast, Ishmael,” said a voice worn into a sing-song by the repetitiveness its daily routine.

“Just put it there on the settee, will you?” This dry voice spoke wryly and precisely.

“Of course.” The first voice chuckled, and those ringing footsteps crossed the remainder of the distance without hesitation. “Would you like your serviette tucked into your collar, as well?”

“No, no, that won’t be necessary.” Stoneware clinked as the tray was set down. “Now, what have we today? Oh, feels like ... eggs ... fresh, I’d say, and over-easy ... hmm, but bigger than usual.... Colin, you haven’t been dipping into the goose nests again, have you?”

“Who, me? Why, of course not.”

“Goodness, man, what will the lieutenant say? And this ... my nose tells me it may be bacon, but the texture is not coarse enough. It can’t be ham, can it? Eh, Colin? And this carafe is too heavy to contain mere water.”

“Go on. Taste it.”

A clink and a faint slurping carried through the darkness. “By thunder, Colin, this is fresh cream. You’re certainly taking risks today, my friend. To what good fortune do I owe this morning’s sumptuous feast? Have you taken a mistress?” A note of sly complicity entered the voice. “Is that why you feel so ... expansive today?”

“Hardly, you degenerate. We’re celebrating you today, Ishmael. It’s your anniversary.”

“Anniversary? Why should I want to celebrate my anniversary? Didn’t you tell me—two, three years ago?—that my wife had finally set her back to this sad little duchy?”

“Not that anniversary. A more important one now. It’s five years today that you’ve been with us as a client.”

“Oh. That. A hollow cause for celebration if ever I heard one. Am I to be fêted then with nothing more than extra rations, Colin? Come, why not unfetter these poor ankles and let us dance to the occasion?”

“Because the duke no longer entrusts that particular key to my keeping after the uproar you created last time.”

“Colin, that was over two years ago! Where is your compassion, my good friend?”

“Don’t start with me, Ishmael. And if you’ve nothing better to do than complain after I risked another reprimand on your behalf, then I have other clients to attend to.” The metallic tread receded.

“No ... wait. I apologize. I know you do all within your power. I am ... grateful for it.”

The footsteps halted.

“Have you any news today, Colin?”

A sullen pause followed. “Have you any new stories for me?”

“I asked first.”

“Oh ... all right.” The footsteps returned. “Old Bradford Smith lost his hand in a cauldron of molten lead last afternoon.”

“Goodness.”

“He did not actually lose the hand in the cauldron, of course, but it had to be removed nonetheless. Oh, and the scrivener’s daughter was found with child.”

“Yes? What a disgrace to poor Benjamin. No connection with Bradford’s hand, I presume. No, of course not.” A light sniffle could be heard in the chill darkness. “Anything else? How is your father’s dropsy?”

“As nasty as ever.”

“And your lovely wife?”

“Serena is quite well, thank you. Oh, by the way, the captain of the guard still inquires after you daily.”

“Yes?”

“Yes. He hopes you’re alive and well and rotting in your torment.”

“Send him my regards, as well.”

“I shall. I only wish I knew what that whole business was about. Now, to our business...”

“What, Colin? Oh, of course, of course, today’s tale. You are an insatiable one. But first—oh, my, this is excellent ham—first, would you be good enough to help me set the stage?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Colin, you know this corner of the dungeon quite well, do you not?”

“Oh, yes. Twenty paces wide, forty long, just enough distance to provide the appropriately sinister echo effect. Twenty-seven paces from the door to your pallet, with a bit of a turn at—”

“Very good. Tell me, do you know the location of the three sconces set into the wall away from the door?”

“The east wall? I haven’t lit those torches since the order three years ago...”

The dry voice snorted. “Measures to reduce my mischief. As if I should be satisfied with this lot.”

“Em, I believe I still recall where they are.”

“What? Oh, oh, yes, the sconces. Would you be so good, Colin, as to walk directly toward the southernmost one.”

“Walk—? What for?”

“Trust me, Colin. You will require the cold touch of brass beneath your hand if you are to fully appreciate the tale I will spin for you this morning, which I call ‘The Sad History of the Nobleman’s Son and the Brazen Chatelaine.’”

“And how late did you stay up devising this story, Ishmael?” The tread echoed off in the appropriate direction. “How many nights— By the gods!” This last exclamation was accompanied by the resounding crack of bone on stone.

“Dear Jove, Colin, that sounded like a nasty fall. Are you hurt badly?”

The response was snappish and gruff. “Who says I’m hurt at all?”

“Tsk, tsk. If I needed any confirmation of the fact, the strain in your voice would do quite nicely. It tells me you are in pain as plainly as if you had spoken it outright. And that sharp cracking sound of a moment ago, combined with the fact that your voice is coming from about knee-level, would lead me to believe that you may have broken an ankle. Colin? No need to hold your tongue, my friend. Your silence speaks more eloquently than any words.”

Indrawn breaths hissed with pain in the darkness. “There’s a hole here in the floor the size of an infant’s casket! I certainly don’t remember this being here!”

“An infant’s casket! How very imaginative and descriptive! I had never supposed you so clever, my dear friend! What a delightful surprise!”

“You mock me, Ishmael. I helped to bury poor Goodwife Miller’s tiny son not a fortnight past, in case you had forgotten.” Bitterness filled the voice. “And you must have known the hole was there. You directed me straight to it.”

“Really? And how would you substantiate such an accusation? How could I have known of any hole in the floor?”

“It was never there before.”

“I don’t see how you can state that with such certainty, Colin. But wouldn’t it be wise to see about getting that ankle attended to?”

“I see what you’re about, Ishmael.” There came a heavy sliding across the stones of the floor, and a grunt. “You’ve managed to get free of those shackles somehow. You want me to believe you’re locked up nice and tidily over there on your pallet, while in reality you’re free to rove about in the dark at your pleasure.”

“Is that so? I believe we have established on more occasions than one, dear Colin, that you are not a clever man. Then how is it that you persist in spinning these elaborate little fantasies? Why, you seem almost to want to usurp my rôle as storyteller!”

“You can’t escape from here, you know.” The slidings continued, and the voice receded in the darkness. “Mock me if you must, but even if you could wrest the key from me and get through that door, you could never pass the guards at the head of the stairs.”

“I have no intention of escaping. Nor do you, obviously, or you would be groveling your way in the direction of the door, rather than following your current heading.”

“I am heading for the door, you pompous ass—and I’m not likely to forget that this ‘pitiful groveling,’ as you call it, is your doing.”

“Ah, but are you certain of that? Are you certain of either point, Colin? First, that your sadly broken ankle is, in fact, my doing—in which case I must be free of my fetters in order to have carved that foot-deep hole out of the floor—or second, that you are really on a heading for the door, since you seem to be orienting yourself solely on the basis of the origin of my voice—with the assumption, of course, that I am still seated in my accustomed spot on the pallet.”

“I don’t need any voice to guide me.” The voice was curt, brusque. “I know where I am.”

“Then you are wiser than the wisest man among us, who would never presume to claim such knowledge. And it therefore puzzles me greatly that you changed your course even as you spoke. This would seem to contradict your statement.”

“You’ve moved, damn you, Ishmael! I can tell from the sound of your voice!”

“I won’t deny it. But neither will I confirm it. Conversely, however, I can tell from the sound of your voice that your ankle is not growing any more well. In fact, I’d judge that you’re not doing it much good with your aimless wrigglings through the dark. Is it beginning to swell yet, do you think, Colin? Are the jagged ends of the bone sawing their way through tendons and ligaments with every desperate move?”

“Stand still!”

“Really, Colin. The beginnings of panic?” The dry voice was suffused with condescension, with stern disapproval. “How very, very unbecoming you. I would have expected better. Especially seeing as I haven’t moved an inch.”

The heavy, labored breathing gradually slowed, but still hitched in pain. “I’ve been your best friend these past five years, Ishmael—your only friend. Is this how you repay me for the extra rations at breakfast? For letting you stretch your legs when I used to carry the right key? For listening to your bloody stories every day when I have other duties to attend to? I’ve endured reprimand after reprimand for your sake, Ishmael. What more do you want from me? What sort of game are you playing?”

“Steady on, Colin. Try not to cast about this way and that as you speak. You need feel no compulsion to address all four walls at once. I assure you that I exist in only one location a time. And I fear that if you keep up this way, your ankle will never forgive you the punishment. I fear you may walk the remainder of your days with a limp.”

“Just answer my question!” A sharp rasp had entered the voice. “And for the love of God keep yourself put!”

“You know, Colin, you’re no great fool, but you certainly do lack that elusive spark we call imagination. Answer your own question, for heaven’s sake. Here we find ourselves, trapped together in a darkness from which you yourself say there is no possibility of escape—”

“None for you, you thankless bastard.”

“Granted, none for me. That being so, what could I possibly gain from playing any sort of game?”

“As you say, Ishmael, I haven’t the imagination to answer that.”

“Do I detect a note of bitterness in your voice, my friend? A note of sarcasm, perhaps? Think on this. Why should I seek to throw off these fetters of mine when it gets me no closer to escape? What would ever drive me to such lengths, which would require that I shatter the bones of my own feet against the stones of the floor in order to slip them through their iron collars?” A rattle of chains penetrated the darkness. “What power would enable me to sit here perfectly still for the perhaps close to a year necessary for my misshapen feet to mend, however imperfectly, and what unimaginable compulsion could impel me to teach myself to walk upon those deformed lumps of flesh once the mending was complete, let alone teach myself to move about silently on these wet stones?”

“God in heaven.”

“Yes, Colin, I find it difficult to imagine it all myself—as it would also entail betraying none of this to you on your twice-daily visits to my little hell.”

“Surely you haven’t—”

“Nothing is sure in this world, Colin. This chamber was carved out of limestone, and the floor filled in afterward with broken rock and mortar to a depth of at least eighteen inches. Surely I haven’t located a place where dripping water has eaten away at the stone and softened the mortar? Surely I couldn’t have managed to pry one of those stones loose from the floor? Surely I wouldn’t have persisted in such a mad task to the point that there now exists a hole—how did you put it?—the size of an infant’s casket in the floor? Surely I haven’t littered its bottom with my bloody fingernails, and I most surely have not retained any of those stones—particularly not for use as a weapon.”

“You’re mad, Ishmael. I hope you realize that I carry ... both a dagger ... and ... a club.” This sentence was punctuated with short, pain-born gasps of air.

“How very nice for you, Colin. Yes, I would have to be mad to oppose a man such as you with only stones in the darkness. And I would have to be especially mad to have gone to such trouble as I’ve described with no reasonable hope of escape, wouldn’t you say? By the way, you should know that I hear you inching your way toward the wall. I hope you realize that if I did happen to possess a cache of stones, those sounds of yours would lend me as clear a target as if we stood under a noon-day sun.”

“Then kill me and be done with it!” The breaths came hard, short, and fast. “Have your fun and get it over with!”

“Oh, how you misjudge me, my friend. We have so much still to discuss. You really wouldn’t want to miss out on it. Tell me, Colin, you’re not beginning to hyperventilate on me, are you?”

“Of course ... not. Don’t be ... ridicul— Aaaaah!”

The cry echoed away into silence.

“Ishmael!”

“Yes, Colin? Did something frighten you?”

“You—you touched me! You touched my face!”

“I don’t see how I could have, not seated all the way over here with these bothersome fetters shackled ‘round my ankles.” The chains rattled once again. “No, I don’t accept that. I don’t see how it would be possible.”

“You lie! You crept ... all the way ... over here and you ... you brushed my face ... with the back of your ... your filthy hand!”

“Shall we take a moment and calm ourselves down, Colin? Did you hear me move at all?”

“No, I didn’t ... didn’t bloody hear you ... move, you ... you bastard!”

“You’re going to have to get that breathing under control, my friend, or you’re liable to pass out right where you lay. Now think for a moment. I can hear you perfectly well when you move. If I were able to move, wouldn’t it be true that you’d be able to hear me as well as I hear you?”

“I don’t believe that ... for ... for a moment!”

“Don’t you? Do me a favor, Colin. Take a deep breath ... let it out ... and turn your head toward the sound of my voice.”

“Go bugger yourself.” But the breathing slowed nonetheless.

“I’m afraid I can’t quite visualize such an act, Colin. Perhaps you’d care to demonstrate it for me sometime?”

“I’ll demonstrate my club dancing a jig on your skull.”

“Colin, Colin, you’ve turned your head the wrong way. Toward the sound of my voice, I believe I said.”

“You’ve gotten behind me!”

“That’s ridiculous. Now, toward the sound of my voice.”

“I’ll do no such thing!” The sound of rough sliding began again.

“Suit yourself. And if that’s the direction in which you’d really like to move, then certainly I won’t stop you.”

“I’d like to see you try, anyway.”

“Not just yet, Colin, not just quite yet. First I’m afraid I may have a bit of bad news for you.”

“What—smashed all the bones in your hands to little bits and can’t feed your own flapping gob?”

“Mmm, you’re getting better, I must admit. You’re certainly getting better. But no, I’m afraid it’s even worse than that.”

“Do tell.” There came a grunt, and a vertical sort of sliding sound.

“Yes, worse even than the fact that you’ve managed to prop yourself up against the wall on your one good leg, precisely opposite to the place you would most like to be.”

“Oh, and where ... where would that be?” This sentence was divided by a deep intake of breath.

“I smell your sweat, Colin. Play brave for the moment, but your sweat is filled with the stink of fear. On a diagonal line, you are precisely opposite the door to this chamber.”

“Which would place you somewhere other than the pallet where you claim to be shackled.”

“Take my word for it or not.”

“I’ll take your word for nothing.”

“Easing your way along the wall now, are you? Try not to fall.”

A sudden brassy clang rang through the darkness.

“And watch your head on those sconces. Now take my word for this: your delectable wife Serena seems to have developed a fancy for that ogre of a butcher—what is his name? Oh, yes—Fat Jack Chesley.”

“How could you claim to know such a thing?”

“Oh, I assure you that I know this, Colin. I see it, even now. That brute Fat Jack and your dear Serena are even at this moment engaged in a bit of an early-morning ... pas de deux, shall we say? ... on that ratty old cot he keeps in the room behind his shopfront. How it ever supports his weight... How Serena ever supports his weight...”

“Ishmael...”

“The smell of slaughtered meat wafts all about them, mixing with the smell of their sweat—which only inflames the passion of our good friend the butcher.”

“That you would stoop so low as to drag the good name of my wife into this...” The voice was an enraged hiss. “I should kill you for that.”

“Then, pray, why don’t you?”

“Because I see what you’re trying to do.”

“And what, my clever friend, would that be?”

“You would love nothing better than for me come at you, to step away from this wall, to lose my balance again. No offense, but I don’t believe you’re worth that.”

“Then hear this, and know yourself for both a fool and a cuckold: I can see quite plainly that peculiar birthmark on your wife’s delightful ivory skin, placed where no eyes but yours and God’s should gaze upon it. And Fat Jack Chesley’s, of course.”

“Liar!”

“I hear the panic lurking below the surface of your voice, Colin. You’ve done an admirable job of reining it in since it last betrayed you—but I just wonder how much prodding it will take to bring it out again? Do you deny that Serena has such a birthmark, Colin? Would you like me to describe the shape of it to you? Or possibly to describe the way it moves beneath our friend Fat Jack’s ungentle ministrations? Colin? Dear friend?”

“You spied on her, you bastard!” There was strenuous breathing, and the sound of cloth sliding roughly across stone. “Before you were arrested! You spied on her at her bath!”

“Did I, now? Shall I describe the sounds of her ecstasy, Colin? My ancestors came down from the North Countries, you see. The Sight has always run in our family. You remember the Sight. It figured quite prominently in that tale of mine you loved so dearly, ‘The Improbable Friendship of Jolly Roger and Sir Thomas More.’ Oh, yes, the Sight is real, Colin, and were it not for that blessed gift I’d have gone mad in this darkness long ago. As it is, I spend my days gazing down on the streets and the fields, the homes and the shops, of our humble little village. I watch the doings of our townsfolk, their comings and goings, their honor and their shame, their joys and their sorrows, and it is almost as if I walk among them again. Were it not for that blessed third eye, Colin, I would long since have surrendered my mind to this black hell, and done it gladly.”

“If this is true, then why ask me the news of the village every day? Eh?”

“To confirm that the scenes I gaze upon are true! Don’t you see, you cursed blind fool? Don’t you see?”

“I see nothing, Ishmael! You’re a storyteller! That’s all you’re telling, is another one of your bloody stories!”

“I am a teacher, Colin! I have always been a teacher first and a storyteller second! Gods above, can no one in this cursed duchy grasp that simple fact?”

“Ishmael, you—”

“Silence! Do you know the scenes I am most compelled to gaze upon in my misery, Colin? Do you? I gaze upon the grounds of the castle! I gaze upon the green lawns and the cool gardens and the stone benches where once I sat and taught the children of the duke himself! He entrusted me with the education of his children, Colin—with their alphabets and their adding-tables and their addled little brains—and I in turn entrusted him with a secret which I risked all my standing and position to relate! I risked it because it was true, and the truth is the only thing in this world which has ever been of any importance! I still gaze down upon that foul labyrinth of shrubbery in which I first chanced to spy the duchess ... and the captain of the guard ... flagrante delicto, as they say. Still I follow the twists and green turns of those hedges to the center of the maze, to the accursed, inviting bower there at its heart...”

“I should not hear this, Ishmael...”

“You shall hear this! You cannot cover your eyes in the darkness! Do you know that the duke refused to see, even as you refuse to see? Even as I am not allowed to see? Surrounded only by light, and you both refuse to see! You all refuse to see! Here is Ishmael, the disinherited son! I am not a storyteller, Colin! I am a teacher!”

This assertion reverberated into silence.

Quiet and dangerous, a voice broke the stillness. “Perhaps you should not seek to teach men lies about their own wives.”

A sudden loud crack resounded in the darkness, followed by a ringing clatter across the stones of the floor.

“Had your dagger out did you, Colin? Good luck finding it now. I’ll teach you about your beloved wife. Oh, yes, there is much I can teach you about the winsome and welcoming Serena.”

“You struck me, you bloody bastard.” The voice was nearly inaudible, lost in wonder. “You struck my face. Why, you...”

“I will teach you what the butcher has learned, what the baker has learned, what the thrice-damned candlestick-maker has learned. I will open your eyes, Colin. You are far too trusting, and I will teach you to trust no longer. I am a teacher, my friend. My life is worth living only when there is a lesson to impart, and the sole remaining lesson I have to share with you today concerns the complete ... and utter ... folly ... of ... trust!”

Another sharp crack, like a shot in the darkness.

“Bastard!” Two quick metallic footsteps sounded, only to be followed by a cry of pain and a heavy crash.

“Forgot about that ankle for a moment, did you, Colin? Now roll over! Roll over, you worthless sack of dung!”

“Get off me, you—”

“Do you feel this below your eye? Do you?”

“For the love of God, Ishmael, let me up!”

“Ah, it seems this dagger of yours has turned out to serve a useful purpose after all. Better than letting it rust in the dampness, don’t you think?”

“What are you doing? What are you doing?”

“Nothing ... yet. And if you will only cooperate, I will need do nothing. We shall recite your lessons now, Colin. You will repeat after me precisely what I say, and we will repeat these lessons until you know them by heart. Do you understand? Won’t this be amusing?”

“Don’t take my eyes please in the name of God don’t take my—”

“Hold still and get a grip on yourself or there may be an unfortunate accident. You are certainly the least clever pupil I have ever had the misfortune to keep in my charge. Now, are we ready? After me, then: ‘There is no power on earth I may safely trust, not even my own.’”

“Ishmael, for the love of—”

“Colin...”

“No more no more no more no more no—”

“It’s only a small cut at the side of your nose. Merely a bit of incentive. Now let’s try this again: ‘There is no power on earth...’”

“‘There is no bloody power on earth...’”

“‘...I may safely trust, not even my own.’”

“‘...I may safely trust, not even my own.’”

“Very good—though this might be easier if you try to relax a little. Good. Now, second: ‘I may never trust any person in authority, for authority cripples the mind and cankers the soul.’”

“‘I may nev—’” A deep, shuddering breath was taken. “‘I may never trust any person in ... in authority, for authority...’”

“‘...cripples the mind and cankers the soul.’”

“‘...cripples the mind and ... and ... and cankers the soul.’”

“Very, very good, Colin. You may just turn out to be a successful student after all. Now, third: ‘I may never trust the fairer sex, particularly when bearing a birthmark shaped to resemble—’”

“Enough!”

There followed a quick whisk of air, a sickening crunch, and a hoarse cry of outrage and pain. Metal clattered upon stone.

“Gods, Colin, you—!”

“Ha! You left one out, Ishmael: ‘I may never trust a student with a club’!” The voice cackled with harsh laughter. “I hope your wrist will forgive you.”

“You’ve sewn it up for yourself now!” Footsteps stumbled drunkenly backward across the stones. “I can move like a ghost in this darkness, Colin! I’ll take you apart piece by piece! I’ll do it at my leisure! You’ll never know what direction—”

This sentence ended with the resounding crack of bone on stone.

“Dear Jove, Ishmael, that sounded like a nasty fall!” The voice cackled wildly. “Are you hurt badly?”

“You ... you...” These moans degenerated into torturous gaspings for air.

The rough sliding sound of earlier resumed, punctuated at times by mad giggles. It proceeded to the wall and then turned left, angling left twice more as it reached corners in the walls. A rusty scrape followed shortly, metal ground harshly against metal, and the bolt of the lock shot back with the sound of a musket being fired in a small room. The door creaked as resonantly as if it opened into the throat of some monstrous bullfrog.

“The saddest part of this all, Ishmael, is that you were scheduled for release this week.” The giggles ceased, and the voice was filled with a sudden deep weariness. “I wasn’t supposed to tell you that, but...”

There was a heavy rustling of fabric, and then the door slammed shut.

“You lie, Colin.” The dry voice was weak and reedy, but gained strength rapidly. “Any child could see through such a transparent fabrication. It’s a story, it’s a story, it’s only a funny story!”

A tired, muffled voice found its way back through the door. “You know me, Ishmael. I’m not clever enough to make up stories.”

“Colin! Colin! Come back here, Colin! ... Colin?”

But the only answer forthcoming, steady as the beating of a heart, ceaseless as the motion of the stars, was the incessant drip! drip! of limewater on stone. ∅

Author

Hugo and Nebula Award nominee. Creator of Proper Manuscript Format, Spelling Bee Solver, Tylogram, and more. Banned in Canada.

Sign up for William Shunn newsletters.

Stay up to date with curated collection of our top stories.